Executive summary

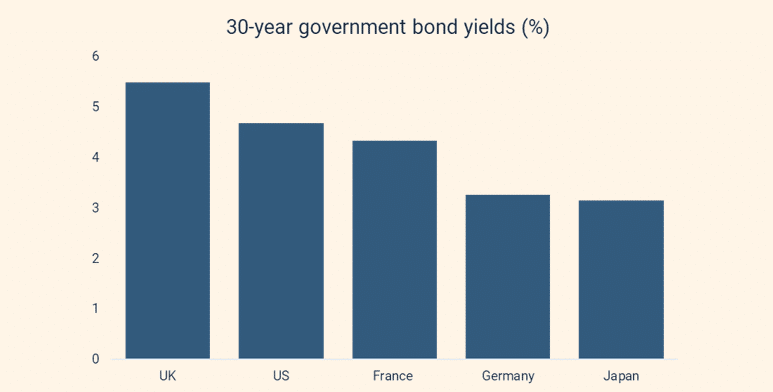

Long-term government bond yields have surged in 2025, rattling investors from Tokyo to Toronto. While this is partly a global phenomenon tied to swollen debt burdens, stubborn inflation and changing investor attitudes, the UK has been hit particularly hard: its 30-year gilt yields have reached levels not seen since the late 1990s.[1] The result is an escalation in borrowing costs for governments, corporations, and households—and in the UK, a narrowing of fiscal space ahead of a crucial 2025 Autumn Budget.

This article explains why yields are rising, what it means for holders of fixed income, why the UK is in especially bad shape, and our exposure to government bonds as we head into 2026.

Source: Bloomberg, Saltus

Why are bond yields rising?

To someone not steeped in bond markets, the constant talk about “yields rising” can feel like jargon. So first, a quick refresher:

- A bond is a form of loan, with the borrower promising to pay interest (the “coupon”) and return the principal at maturity.[2]

- The yield is the effective interest rate an investor will receive, factoring in the coupon, and current price vs. face value.

- When yields go up, bond prices go down, and vice versa.

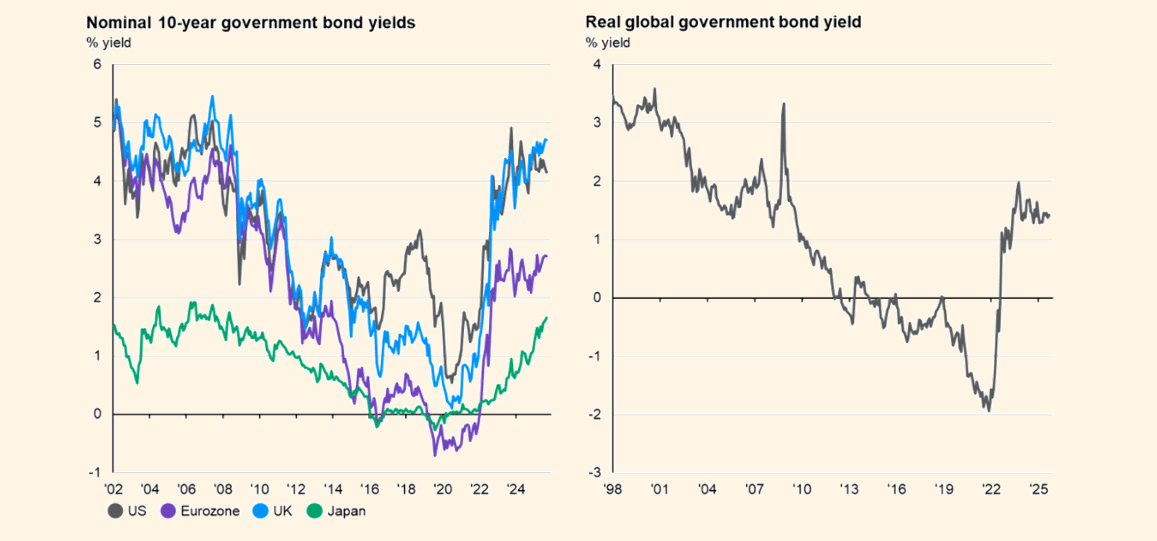

- In 2025, yields on long-dated government bonds (over 10 years to maturity) have climbed sharply across many advanced economies. For example, U.K., German, Japanese and French long-dated yields have all touched multi-year highs.[3]

Source: J.P Morgan Asset Management – Guide to Markets UK Q4 2025 [14]

What’s behind this broad surge? Several reinforcing factors:

- Inflation worries and “higher for longer” rates

Investors are fretting that inflation will remain persistent, forcing central banks to keep interest rates higher for longer. When inflation expectations rise, investors demand higher bond yields to compensate. In the UK, inflation is currently almost double the Bank of England’s (BoE) target, hovering around 3.8%.[4]

- Policy signals and central bank balance sheet operations

Many central banks are reducing their bond holdings (a process often called “quantitative tightening” or QT). When a central bank sells bonds, or stops reinvesting maturing ones, it increases the supply of bonds in the market – pushing their prices down and yields up. In the UK, in particular, the Bank of England’s balance sheet reduction has drawn scrutiny as a contributing factor to gilt market volatility.[5] [6]

- Expanding government debt issuance and fiscal concerns

Developed world governments are issuing ever more debt to fund fiscal deficits. For instance, the US ran a $1.8 trillion deficit last year, and the UK’s debt-to-GDP ratio is nearing 100%.[7][8] Higher issuance means more supply of bonds competing for investor capital, putting downward pressure on prices (i.e. upward pressure on yields). In some cases, the markets are questioning the sustainability of fiscal policies – especially apparent in the US, UK, and France, where “budget woes” have combined to create bond market turbulence.[9]

- Global contagion, investor repositioning, and rising term premium

Bond markets move in a web: stress in one country spills into others. Some investors are de-risking, shifting away from longer maturities or perceived weaker credits. Investors are demanding more compensation for holding long-term debt, especially amid political uncertainty and ballooning deficits.[10][11]

- Narrative and sentiment shifts

Bonds are often sensitive to narrative: when investors start worrying about a country’s fiscal credibility or political stability, even if the fundamentals are ambiguous, yields can move aggressively. Unpredictability and uncertainty make bond markets more fragile.

Impact on investors

Rising long-term yields carry a wide set of implications. Some are obvious, others subtler. Here’s what to watch:

- Existing bond holders take a hit (capital loss)

If you bought a 30-year bond at a yield of 3% and now market yields jump to 5%, your bond’s market value falls. If you sell before maturity, you suffer a capital loss. That’s painful for fixed-income funds, pension funds, insurers, and individuals holding bonds.

- New issuance becomes more expensive

Governments and corporations must pay more to issue debt. A company that might have borrowed at 4% must now promise, say, 5–5.5%. Higher cost of capital filters into investment decisions, project viability, and borrowing appetite.

- Refinancing risk and rollover risk

If an entity has to roll over existing debt (i.e. repay maturing bonds by issuing new ones), the elevated yield environment is a threat. The new issuance costs more; margins get squeezed.

- Effects on fiscal and monetary policy

If governments are forced into austerity (cutting spending, raising taxes) due to debt service burdens, that might dampen growth or inflation. Conversely, pressure on central banks to avoid yield spikes may influence their rate decisions.

- Opportunities for investors

Not all is doom. Higher yields mean more attractive entry points, especially for long-term investors. If an investor will hold the bond until maturity, and there is low default risk, this is a relatively low-risk way to provide an income.

Do you need help managing your investments?

Our team can recommend an investment strategy to meet your financial objectives and give you peace of mind that your investments are in good hands. Get in touch to discuss how we can help you.

What’s happened in the UK?

What’s special about the UK’s case

Yes, bond yields are rising globally. But in the UK, the pain has been notably sharper and amplified by domestic factors.

- Fiscal credibility doubts and budget hole fears

Investors are increasingly worried that the UK’s government is out of fiscal headroom. There’s a perception that past fiscal forecasts and growth projections have been overly optimistic. Given these concerns, foreign investors demand a higher risk-premium for holding UK government debt. This has the potential of becoming a vicious circle, as higher yields result in higher debt servicing costs, especially as the average maturity of UK government debt is 14 years, almost double the average for the other G7 members. The UK already spends more than £100bn per year in interest costs.[12]

- Bank of England’s balance sheet reduction

The BoE’s decision to unwind holdings (i.e. sell gilts or let them mature) is seen as exacerbating downward pressure on gilt prices (i.e. upward on yields). Some have cautioned that this is worsening gilt turbulence. Indeed, ex-MPC members have publicly urged the BoE to slow or halt its bond-selling plans, arguing it could save the Treasury up to £10bn per year.[13][14]

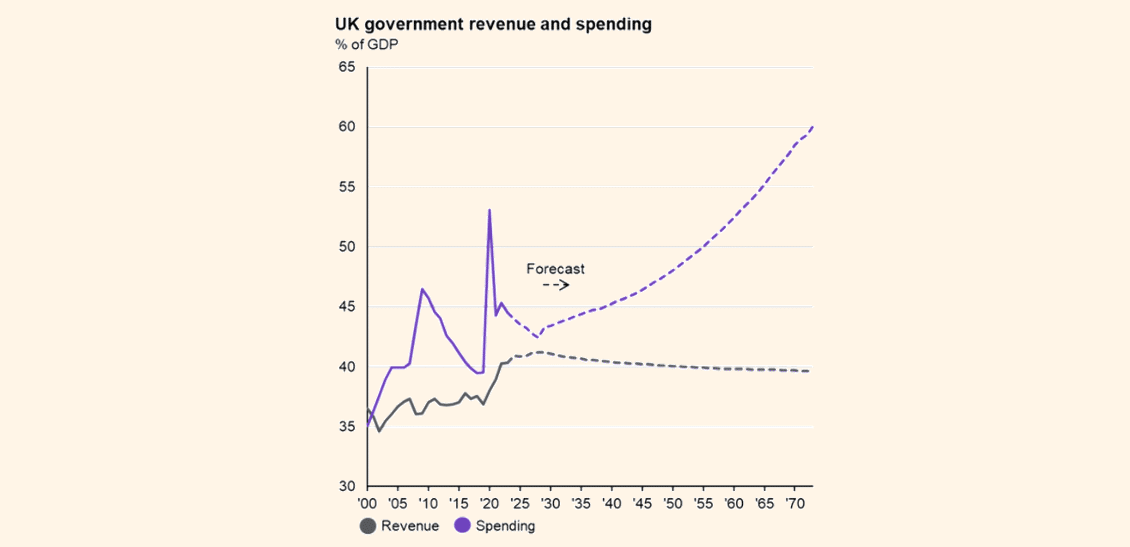

- Structural weaknesses: low growth, weak productivity, aging population

Over the past 15 years, UK productivity growth has been lacklustre. That limits growth potential and constrains the ability to carry a large debt load. Also, demographic pressures from an aging population – which impacts healthcare and pension spending – are adding to the debt burden.

- Narrative and political risk

The bond market doesn’t just price hard data — it prices confidence (or lack thereof). Speculation around ministerial changes, policy consistency, and fiscal credibility feed into yield volatility. For instance, during just one Prime Minister’s Questions, the mere possibility of replacing Rachel Reeves triggered a gilt market sell off.

In short: the UK is being punished more harshly because the bond market doubts its margin for error.

Source: J.P Morgan Asset Management – Guide to Markets UK Q4 2025 (14)

What the 2025 Autumn Budget might mean

Given heightened market anxiety and rising gilt yields, the 2025 Autumn Budget (scheduled for 26 November 2025) assumes outsized importance. Here’s what to watch — and what could happen:

- “Tinkering will not do”

The government must convince markets it can stick to fiscal discipline, with bold, decisive action. This may require tough decisions: spending cuts, tax rises and structural reforms.[15] - Revenue-raising vs growth sensitivity

The tricky balance: raise tax revenue without suffocating growth. If tax hikes disproportionately harm investment or employment, they could backfire, necessitating further borrowing. The misstep will intensify the “doom loop” dynamic.[16][17] - Shape of tax reform

Speculation includes possible property taxes, land taxes, or measures that shift revenue burdens in less growth-distorting ways. One idea commonly floated is using land taxation (because land supply is fixed) to raise revenue without depressing labour or capital investment. - Debt issuance strategy and maturity mix

The government could rebalance its issuance toward shorter maturities to lower interest cost risk (though that increases rollover risk). It may also reduce longer-dated issuance if investor appetite is weak. - Support from monetary policy

The BoE might signal a more accommodative stance on quantitative tightening (QT) or even slow bond sales to ease gilt yield pressure. Indeed, some relief was seen when Governor Bailey hinted at reductions to the bond-selling program, helping yields modestly. - Buffer and unexpected shocks

The government may build a contingency buffer (e.g. windfall taxes, reserves) to absorb shocks. But with markets already jittery, surprises will be costly.

If the Budget fails to reassure investors, gilt yields could spike further, borrowing costs balloon, and the government may face a fiscal squeeze so severe that it constrains policy choices for years.

What is the Saltus approach to government bonds?

At Saltus, we currently have a cautious approach to government bonds, reflecting many of the concerns listed above. Unlike in the past, bonds no longer provide the same portfolio diversification benefits, with stock and bond markets now moving in closer correlation. Instead, we prefer to achieve portfolio diversification through a broader set of alternative asset classes that can better withstand shifting market dynamics.

Where we do hold government bonds, our positioning is deliberate and conservative. The majority of our exposure is in the UK, focused on short-duration bonds that reduce sensitivity to interest rate changes. In the US, we favour inflation-protected securities, offering a safeguard against the persistent risks of rising prices.

We also seek to capture opportunities beyond traditional bond exposure. To this end, we hold a specialist fund employing a long/short strategy in government bond markets. This approach is designed to benefit not from the direction of yields, but from the volatility and dislocations that occur within the asset class. We view this as part of our alternatives allocation, helping to provide clients with returns that are less dependent on traditional market movements.

Conclusions

Rising long-term bond yields in 2025 represent more than a market technical: they are a signal of shifting expectations about inflation, fiscal risk, and central bank resolve. While many developed economies face this challenge, the UK is under particular pressure. Compressed fiscal room, weak growth, and a fragile narrative have made British gilts especially vulnerable.

For investors, the era of “buy it and forget it” bonds is over — risk, duration, and yield sensitivity demand active navigation. For the UK government, the 2025 Autumn Budget is not just another policy event — it’s a credibility test. If markets are not reassured, rising yields could constrain borrowing and force unpalatable fiscal choices.

From here, the path is uncertain. Yields might plateau, or they might surge further if a shock arrives. What seems clear is that we are entering a new regime: one in which capital markets will demand discipline, nimbleness, and clarity from policymakers and investors alike.

Article sources

Editorial policy

All authors have considerable industry expertise and specific knowledge on any given topic. All pieces are reviewed by an additional qualified financial specialist to ensure objectivity and accuracy to the best of our ability. All reviewer’s qualifications are from leading industry bodies. Where possible we use primary sources to support our work. These can include white papers, government sources and data, original reports and interviews or articles from other industry experts. We also reference research from other reputable financial planning and investment management firms where appropriate.