What is the optimal long-term strategy for investing?

Important Considerations

Before we get into the strategy itself, it is essential to cover off a few key introductory points that should always be taken into consideration when investing. To successfully invest for the long term, it is crucial that you have a solid foundation from which you can build. Many of these points may seem straightforward but they are vital for putting your money to work over the long-term, and a financial adviser will easily be able to help with how to approach these.

- Firstly, get your finances in order: having a clear understanding of your assets and debts is very much the first stage of investing. It is the platform from which you will build your portfolio.

- Consider the tax implications: paying an unnecessary tax bill can easily negate hard-earned profits from your investment portfolio. However, if avoiding tax is your primary driver, you may find yourself making decisions that ultimately harm your portfolio’s return. ‘Do not let the tax tail wag the investment dog’.

- Match your investments with your time horizon: this is key to ensuring that you are rarely forced to sell at a loss. In the short-term, markets can be incredibly volatile and hard to predict. Over longer periods, the environment becomes rather more stable. For example, were you to invest in the MSCI World for any twelve month period over the last fifty years, you would have a 74% chance of finishing with more money than you started. If instead you invested over a five-year period, this increases to 87%. Extend this further to a ten-year period and your portfolio would have made a positive return 100% of the time.

Modern Portfolio Theory

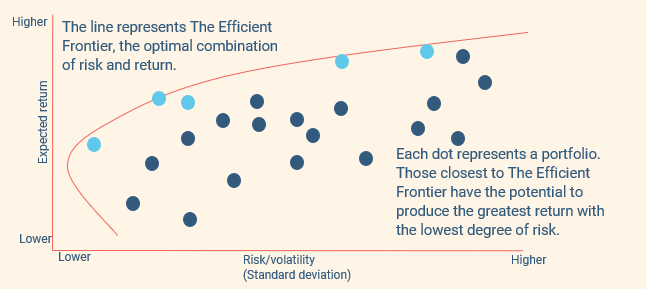

Assuming you have the foundations in place then, what is the optimal strategy for investing? There are a number of theories that have underpinned investing in recent years that may help us discern the best possible strategy for investing over the long-term. Modern Portfolio Theory (MPT) states that for each given level of risk, investors should construct portfolios to maximise their expected returns. To do this, each investment should not be analysed on a standalone basis, moreover, it should be evaluated on how it affects the overall portfolio’s risk and return profile. An asset with a low correlation to the rest of the portfolio may still be beneficial to hold, even if it has a higher risk or lower return than the other constituents. For example, adding 10% of your relatively safe gilt portfolio, into more volatile UK smaller companies, not only increases your potential return but reduces the overall portfolio risk.

MPT states that it is possible for an investor to reduce risk simply by holding a combination of instruments that are not perfectly positively correlated with each other. The less correlated the assets, the greater the risk of the portfolio deviating from a weighted sum of its parts. Two uncorrelated assets may sometimes still move in lockstep (they are uncorrelated not negatively correlated after all). If you extend this to 3 or 4 uncorrelated assets though, the chance of this occurring decreases which, in turn, reduces the volatility of your portfolio.

Using historic correlations, it is possible to build a portfolio that sits on what is known as ‘the efficient frontier’ (the line that maximises returns for any single level of risk). However, this approach relies heavily on the assumption that historic correlations will hold. During the Great Financial Crisis, a number of asset class correlations broke down (by all moving in the same direction at the same time) and offering investors little protection. When investors experience times of extreme stress, there can be a rush to sell almost every asset without much thought to the fundamentals that drove you to hold them in the first place. Relying on the correlation between two distinct asset classes (such as stocks and bonds) to persist in any given environment, can offer less protection than using a broader approach to multi-asset class investing. Since the financial crisis, there has been an over-reliance of the financial system on government stimulus, or Quantitative Easing. This has driven both stocks and bonds to new highs and increased their correlation significantly. Needless to say, the inverse of this can also be true, where correlations remain high but both assets are losing money during ‘Quantitative Tightening’

The Endowment Model

The Endowment Model is used by the largest foundations and universities around the world, which rely on drawdowns to fund their current spending. These endowments strive to meet two chief objectives. Firstly, they aim to generate returns high enough to cover their yearly withdrawals, ideally without having to dip into their capital. Secondly, they aim to preserve the real value of their capital and withdrawals over time i.e., not see them eroded by inflation. These are two targets a lot of people, no doubt, would like to see met by their pension. One very apparent difference between traditional portfolios and the asset allocation of endowments is a much higher weight to alternatives. These could be hedge funds, currencies, private equity or real assets like property and commodities. A common factor for all of them is a lower correlation to traditional markets. Despite individually some of these asset classes having higher volatility than equities, what differentiates endowments from their retail counterparts is their willingness to create portfolios that have a lower risk and higher reward potential than just bonds and equities.

The reason being, if the future of your establishment relies on regular withdrawals derived from the total return of your portfolio, then ensuring capital growth whilst ardently controlling the risk on the downside is essential. It can be exceptionally damaging for a portfolio to crystallise losses in the midst of a drawdown, even if the withdrawal amounts are usually manageable. According to a study by the US National Association of College and University Business Officers, an average annual withdrawal from a university endowment is between 4% and 5%. However, during 2008 this swelled to between 15% and 20% due to an increased level of student financial aid and reduced donations.

What if I don’t need access to the capital and I can handle significant risk?

Interestingly, this is where MPT and the Endowment Model have some limitations. In cases where both the risk appetite is high, and the time horizon is long (no regular withdrawal or income requirements), the focus shifts from the journey to the destination. In other words, volatility takes a backseat in favour of maximising returns.

That is not to say investors should be happy taking a permanent loss of capital, merely that they have a greater tolerance for mark-to-market risk. The key is to stay invested as long as possible. Looking at the MSCI World Index, since its inception, there have been (on average) three to four occurrences per year where it has declined more than 5% and one occurrence every two years where it falls by more than 10%. A fall that was greater than 20% occurs every 6 to 7 years. Price volatility is easily turned into a permanent capital loss if a holding has to be sold before it has a chance to shrug off the short-term sentiment. Over the longer-term, investors are rewarded by accepting this volatility as the long-term growth in corporate profits drives the value of equity holdings higher.

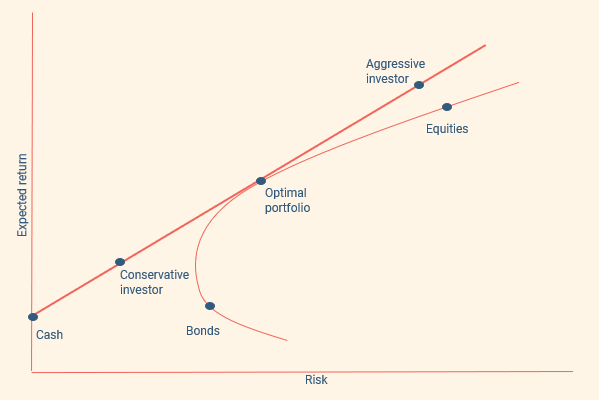

MPT attempts to provide a solution to an investor that is only focused on maximum return with no access to capital needed, by introducing the Two Mutual Fund Theorem (in this case the two mutual funds can be seen as multi-asset portfolios). This theorem states that any portfolio on the efficient frontier can be generated by holding a combination of any two given portfolios that are already on the frontier. If the location of the portfolio on the frontier is in between the two funds, (the conservative investor below) then both will be held in positive quantities (50% cash, 50% the optimal portfolio). If instead, the portfolio is outside of these two (the aggressive investor), then the lower risk fund would have to be held in a negative quantity (-50% cash, 150% in the optimal portfolio). Obviously, in the real world, shorting is not an option for many investors, so the aim instead would be to find the portfolio that sits on the efficient frontier when no cash is held at all.

The Endowment Model is less relevant when simply trying to achieve the highest level of risk and return possible. The constant reliance on withdrawals to fund their spending means that they can never shift their focus from the journey to the destination. If, however, you can suffer full market risk, then cherry picking the highest return assets from the endowment model would be the optimal strategy. As few asset classes have the same growth prospects as equities, this leaves a rather short list.

One stand out asset class from the endowment model is Private Equity. Over the last 30 years, private equity in the US has returned over 13% annually compared to the equivalent public market that returned c.8%. There are a number of reasons for this outperformance, but the most common explanation is that private businesses provide a greater opportunity to add value and find hidden gems (alongside some leverage). Growth prospects for smaller companies remain far higher: it is easier to comprehend a company with a £100 million market capitalisation growing to 100x its current size than it is for a £100 billion company. With that said, private equity investments are far riskier than their counterparts and have a much greater risk of permanent capital loss due to the lower liquidity and high use of leverage. Investments in private equity should make up a small portion of your overall portfolio and be paired with liquid assets to cover commitments and drawdowns. However, if your time horizon is very long, it is a fertile hunting ground for generating returns, many of which have a lower correlation to public equity markets.

Conclusion

Ultimately, there isn’t a singular approach that will apply to all investors. If you are growing your wealth and have little need for it in the short, or medium term (the ‘accumulation phase’) then the key is making sure you are being compensated for your ability to take increased market risk. The aim is to accrue significant gains without spending overwhelming amounts of time sweating over them. By accepting that there will be price volatility, mentally preparing yourself for drawdowns and making sure you have your time horizons clearly set out and regularly reviewed, it is possible to achieve this. Staying invested is key.

However, if like a university there is a requirement in the near-term for some of the capital, or the ‘decumulation phase’, then the optimal long-term approach will most probably be the endowment model. Diversify your portfolio across a large number of asset classes, likely including alternative assets with low correlation to traditional markets to achieve this. Clients who have retired, or are approaching retirement, and need their assets to fund their lifestyle will particularly benefit from this model. Over-reliance on one or two correlations can over-expose your portfolio to unseen risks and black swan events. Once again, staying invested is key, however in this scenario your asset mix will be rather different.

Article sources

Editorial policy

All authors have considerable industry expertise and specific knowledge on any given topic. All pieces are reviewed by an additional qualified financial specialist to ensure objectivity and accuracy to the best of our ability. All reviewer’s qualifications are from leading industry bodies. Where possible we use primary sources to support our work. These can include white papers, government sources and data, original reports and interviews or articles from other industry experts. We also reference research from other reputable financial planning and investment management firms where appropriate.