Summary:

- More people will vote in 2024 than in any previous year

- In a period of heightened political uncertainty

- So elections will dominate the headlines

- But they won’t necessarily dominate financial markets or investment portfolios

- Historically, elections have created volatility around the election date, they rarely change the direction of markets

- Because markets are more impacted by economic variables such as growth, employment, interest rates, and currency movements, and politicians generally have limited impact on these (especially where there is an independent central bank like in the UK and USA)

- Saltus will be watching political developments closely, but we will focus on events that could affect our portfolios and do our best to block out the noise

We take comfort from the fact that Saltus portfolios are very widely diversified, we try and find many sources of return, that are each dependent on different factors, to reduce our reliance on individual companies, markets, asset classes, currencies, sectors… and politicians!

As part of this, Saltus portfolios are typically much more global in nature than many we see (Saltus portfolios generally have less exposure to the UK), and so are less impacted by UK political issues.

The Saltus investment team are watching events unfold, because there is a chance it is different this time, that politics may have an impact on financial markets and portfolios that requires action.

However, the lesson from history would be to block out the noise, not to worry too much about how politics will impact portfolios, however uncomfortable that feels.

For as Robert Arnott said, “in investing, what is comfortable is rarely profitable.”

Read on to find out more…

Do you need help managing your investments?

Our team can recommend an investment strategy to meet your financial objectives and give you peace of mind that your investments are in good hands. Get in touch to discuss how we can help you.

In 2024, countries with more than half the world’s population will vote. In fact, more people will vote in 2024 than in any previous year. [1]

The political back-drop is uncertain to say the least. Eurasia Group have described it as follows:

“Politically it’s the Voldemort of years. The annus horribilis. The year that must not be named.”

“Three wars will dominate world affairs: Russia vs. Ukraine, now in its third year; Israel vs. Hamas, now in its third month; and the United States vs. itself, ready to kick off at any moment.”[2]

How much should investors be concerned about politics? Well, from the point of view of their investments, we’d argue they shouldn’t be hugely concerned. This is based on one fundamental point:

Over the long-term, economics influences markets, not politics

Before we look at elections and politics in general, I wanted to mention wars / armed conflict, because many view this as part of politics (the topic of the article).

A brief aside on conflict

Armed conflict is dominating the headlines.

The current focus is on Russia vs Ukraine, and Israel vs Hamas. But, sadly, it’s hard to think of a time when there hasn’t been a conflict somewhere.

Conflicts do impact economics and markets. But as terrible as wars are, historically, financial markets have shrugged off conflicts fairly quickly, as shown below.

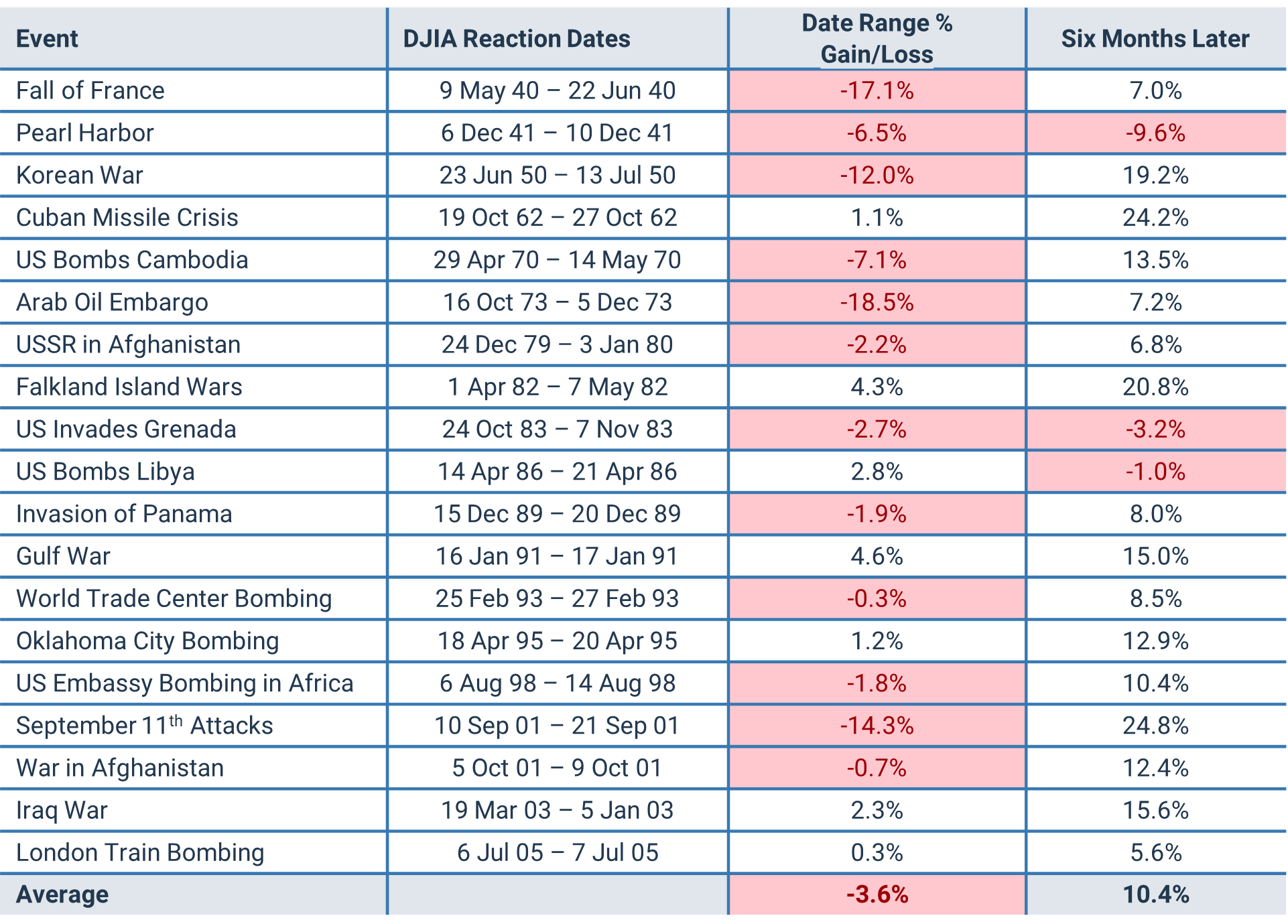

The Dow Jones Industrial Average measures 30 prominent companies listed on stock exchanges in the United States. If you look at how it reacted to historical geopolitical events (shown below), you see its average fall was only -3.6% during the time the market reacted, and in 16 out of the 19 cases, the market was in positive territory six months after the initial reaction. This suggests that markets do react to the onset of war, but they normally recover fairly swiftly.

Source: Amundi, Morningstar and Bloomberg. As of December 31, 2019 [3]

Saltus are not complacent about conflict. We are watching events unfold, and we will respond to emerging threats to portfolios as appropriate.

Elections and markets

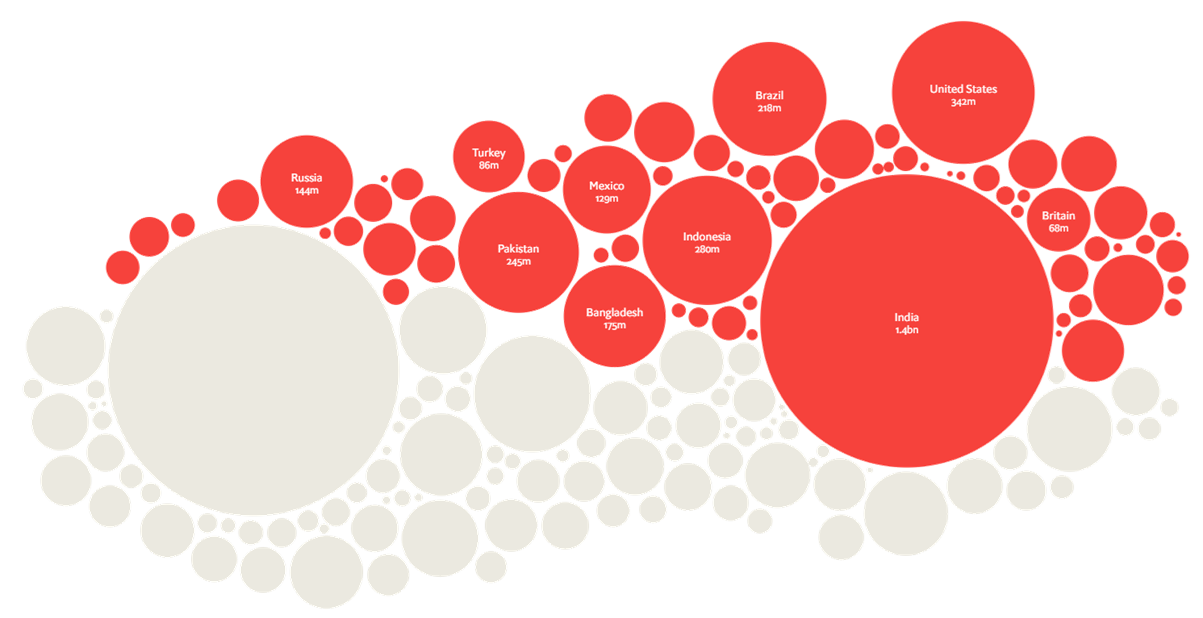

So many countries are voting this year, as you can see in the graphic below, which shows the countries that are having elections this year (in red).

Source: Economist & Economist Intelligence Unit [1]

But not all of the elections are consequential from an economic perspective, for global investors at least.

Firstly because some countries have a greater impact on global trade (e.g. USA is roughly 25% of global GDP, the UK is about 3%). Secondly because some elections don’t change policy, because either the election isn’t free and fair, or because there are limited differences between parties as far as economics is concerned.

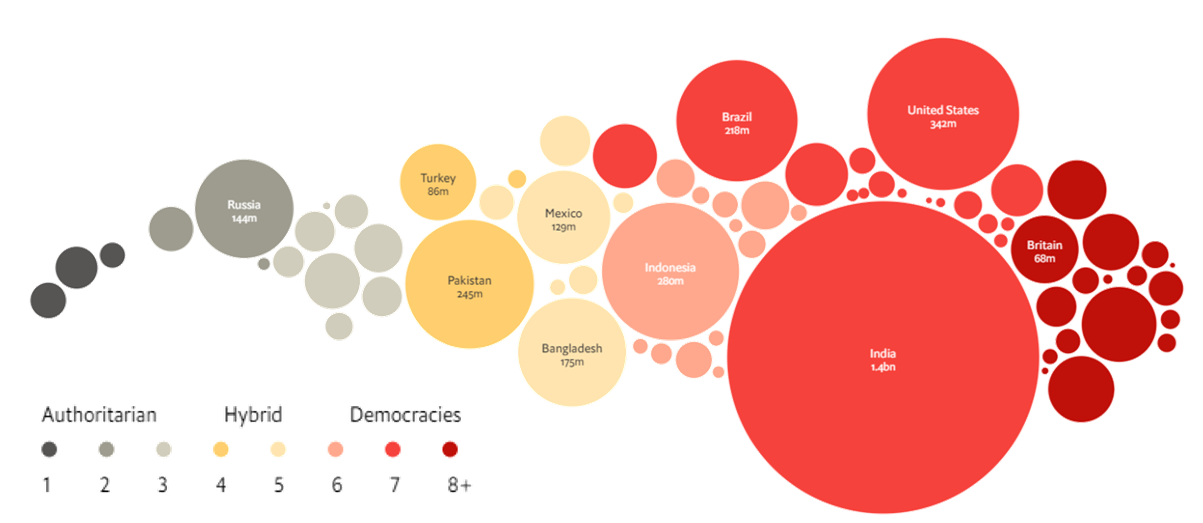

To illustrate the free and fair point, see the updated chart below, updating the countries with 2024 elections with colours to illustrate whether those countries are authoritarian or democratic.

Source: Economist & Economist Intelligence Unit [1]

Britain for example, is highly democratic, and the election will decide the next government and could cause substantial policy change, although we don’t think it will.

Conversely, how surprised were you that Putin won the election in Russia earlier this year?

So, do free and fair elections influence markets?

The evidence (US & UK data) suggests that elections can increase volatility, but 1) the volatility is short-lived, and 2) after the election volatility subsides, the market continues traveling in whatever direction it had been travelling before the election.

In other words, elections can make the journey bumpier but they won’t change the direction you are travelling in. This is because markets don’t care about most policies.

Take, for example, the upcoming US elections, which, according to The Hill, will be fought on the following main issues:

- Social security and Medicare

- Education

- Abortion

- Foreign policy

- Immigration

- LGBTQ-related issues

- Crime

Whilst not trying to minimise the importance of the above issues for those affected. It’s our view that foreign policy is the only one likely to affect the outlook for financial markets for globally diversified investors like ours.

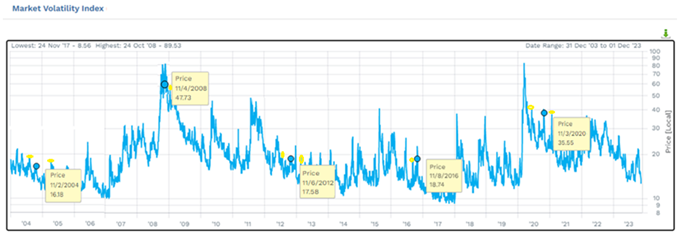

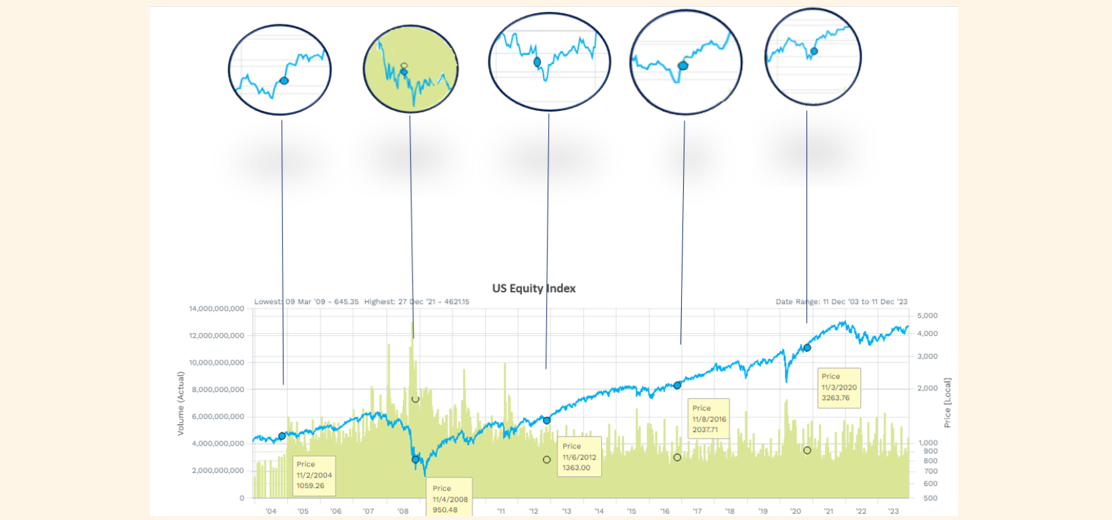

Factset studied the volatility of US stock and bond markets around US elections over the last 20 years. A summary chart is shown below. The blue line represents the volatility of the US equity market over time. The higher the blue line the higher the volatility. The blue dots (labelled with yellow boxes) are when each US election happened (every fourth November).

Source: Factset [4]

In the chart you can see localised increases in volatility around election days. However, the blue dots (elections) are not the highest peaks in any of the years (apart from arguably in 2008 but the volatility was from a financial crisis, not because of the election). Factset concluded:

“The impact from elections on market dynamics is not in any way exceptional. The dynamics and direction of the markets seem to be influenced more by macroeconomic factors such as inflation, interest rates, foreign exchange rates, or economic growth.”

In addition to looking at volatility, Factset looked to see if the election changed the direction of travel for the US stock market. They did this by studying the market trend before, during, and after elections, summarising:

“Looking at the charts below for the last 20 years of market responses before/after elections, the market continued to follow the trend, which is displayed before election days. Equity and high yield bond markets trended upward in 2004, 2012, 2016, and 2020 and trended downward in 2008. US presidential election outcomes did not revert this longer-term trend in the market.

The circular pop-outs for each of the election days, depicted by the blue dots, provide a zoomed-in view of approximately one month before and one month after each election. We notice signs of short-term volatility observed in the dates around each election. However, beginning a few days or weeks after the impact is no longer observed, the longer-term trend resumes.” (Emphasis added).

Source: Factset [4]

If not elections, does politics influence financial markets?

If elections themselves don’t particularly matter, does politics matter in general?

Governments are generally responsible for deciding how countries are run, for managing things day to day. Setting taxes, deciding how to spend public money, and how to deliver public services. [5]

However, most western governments do not have control over their economy’s monetary policy or how their financial system operates. This power generally rests with an independent central bank (e.g. Bank of England and US Federal Reserve) whose job it is to set the cost of borrowing, manage inflation, and maintain financial stability.

Politicians, at least in the UK and US, do not have the power to make the most important economic decisions. These are done independently.

That said, governments can influence a country’s economy, primarily via taxes and spending, by affecting the supply of goods and services. The more a government spends the larger the boost to economic growth and inflation, all else equal.

However, a government needs to fund this spending from somewhere, either through tax revenues or borrowing the money. But higher taxes and more debt can lower economic growth in the long run and may therefore be counterproductive. As Winston Churchill famously said, “for a nation to try to tax itself into prosperity is like a man standing in a bucket and trying to lift himself up by the handle.” [6]

If politics matters for financial markets, surely we’d see significant differences in market returns depending on who was in power. Let’s look at US and then UK politics.

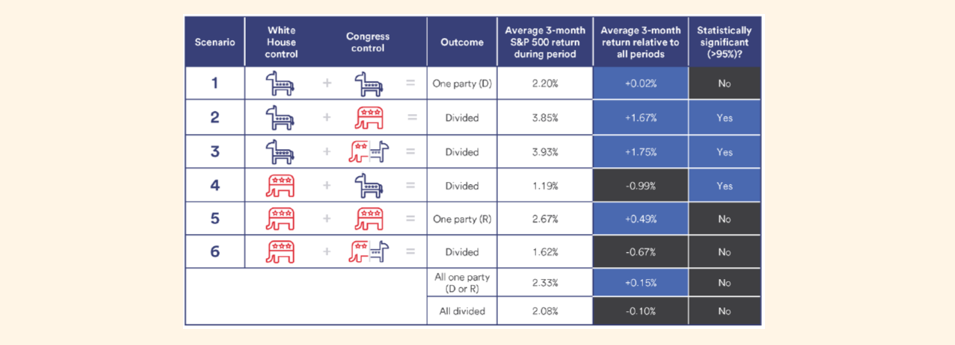

US Bank studied market data going back to 1948. They looked at the average 3 month returns following each US election outcome, and compared that to the average 3 month return during the full analysis history. Whether there was a difference, and whether that difference was statistically significant (i.e. whether one could say with confidence that the result wasn’t random).

Their results are shown in the table below.

Source: US Bank [7]

Of the available combinations for which party controls what, they found only three out of six scenarios were statistically significant for affecting the US stock market:

Two scenarios had been positive, with stock market returns higher than average:

- Democratic control the White House & full Republican control of Congress

- Democratic control the White House & split party control of the Senate & House

One scenario had been negative, with stock market returns lower than average:

- Republican control of the White House and Democratic control of Congress

In other words, even if a party has control of both the White House and Congress (a clean sweep), this hasn’t affected financial markets, even though the winning party would have been better able to set policy. In addition, republican control does not boost market returns as some believe.

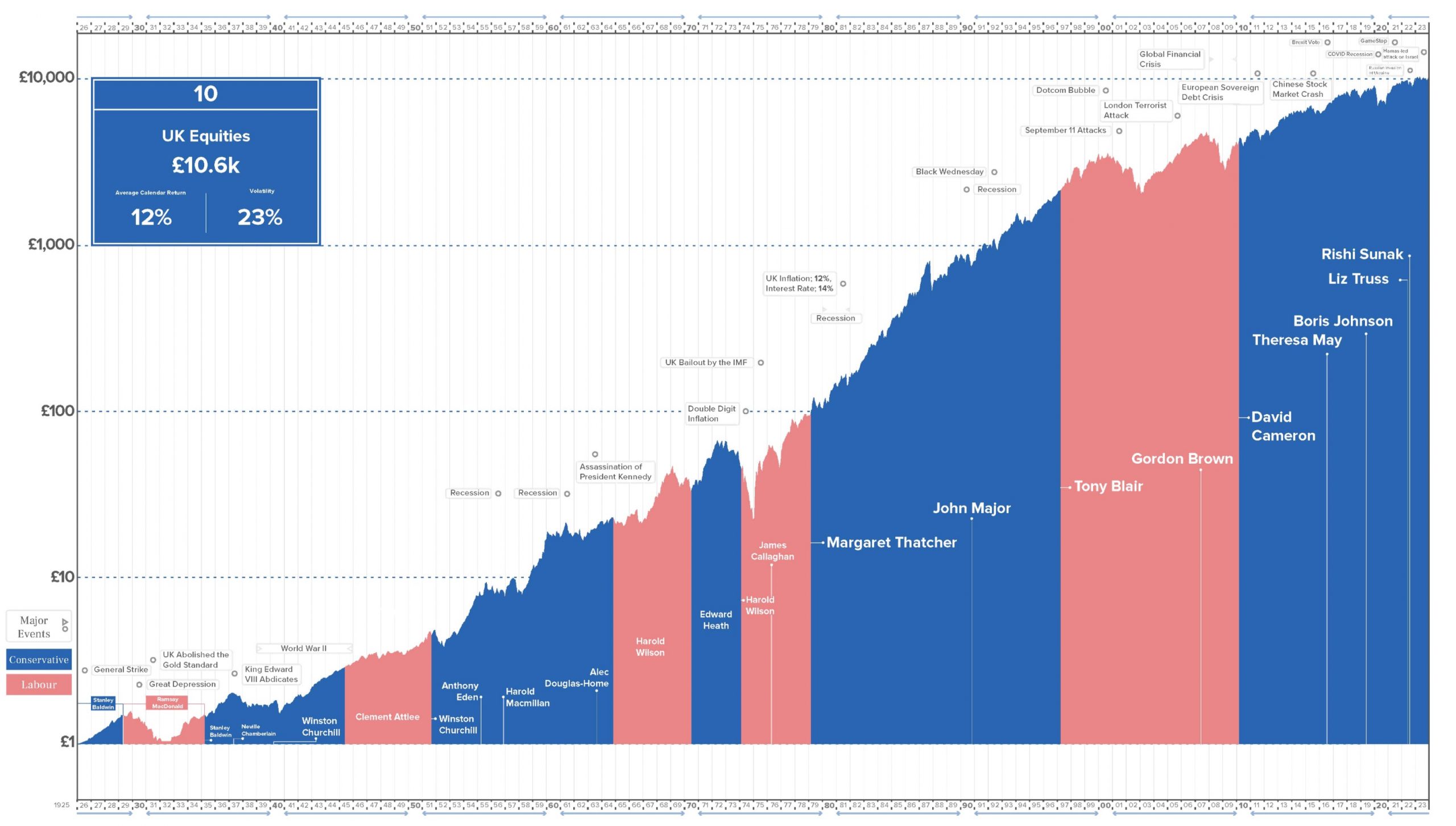

Morningstar conducted similar analysis on the UK stock market, looking at whether UK stocks performed better or worse under Conservatives or Labour. They looked at data going back to 1945 and found that stocks performed better in the twelve months after a Conservative victory than they have after a Labour victory. But they noted that the averages “are heavily skewed by individual instances of bull and bear rallies – in 1974 when Labour was elected to power the FTSE All Share fell 55%, and in 1955 when the Tories won the UK stock market rose an impressive 50%.”

Presiding over a financial crisis, or being in power during the dot.com bubble and its bursting, can make it look like the party in power has performed poorly when in fact they had limited control over the events.

A senior analyst concluded:

“The political machinations in Westminster have little bearing on the earnings potential of UK companies, which ultimately drives stock prices in the long term… So while sentiment may swing, investors should stick to their guns and not let the election clamour distort their savings plans.”[8]

Timeline illustrated the above point by looking at the journey of £1 invested in UK stocks since 1926. A period including the Great Depression, World Wars, terrorist attacks, and financial crises. Calendar returns were 12% on average. £1 would now be over £10,000. Portfolios can make (and lose) money regardless of who is in power.

Source: Timeline Limited using data from Morningstar [9]

If not politics, what influences markets?

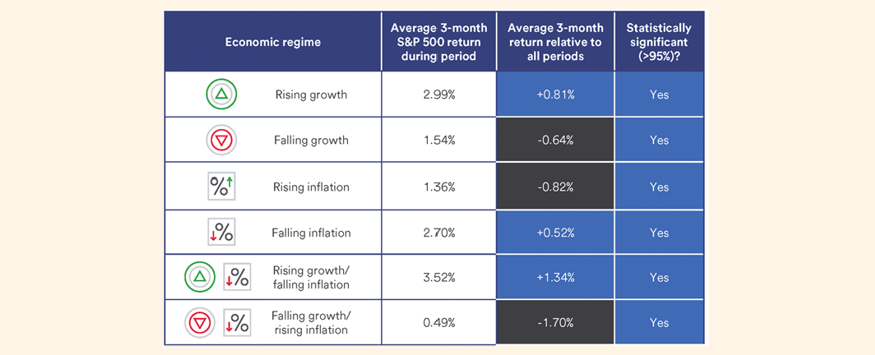

US Bank also studied how economic regimes (e.g. economic growth and inflation) affected market performance. The results are shown below:

Source: US Bank [7]

The table shows that all six regimes had a statistically significant impact on returns (rather than only three out of the six possibilities for the political tests). Economics has more of a significant impact than political parties.

US Bank found that rising economic growth and falling inflation were associated with returns above long-term averages. Whilst the reverse was also true (that falling growth and rising inflation were associated with lower returns).

They concluded:

“The historical data suggests that economic and inflation trends, more so than election outcomes, tend to have a stronger, more consistent relationship with market returns… For investors, staying focused on these patterns is probably more insightful than potential election outcomes when it comes to forecasting market performance.”

Could it be different this time?

Maybe.

The Chairman of the Saltus Asset Allocation Committee wrote in December 2023:

“The big potential shocks of 2024 are likely to be political in nature. Looking at the polling data, the probability of a Trump presidency in the US is surprisingly high. If this were to happen, his policy agenda is very clear and, unlike his first presidency, he appears to be much better prepared with key advisors and appointees in place to implement changes as quickly as the political system allows. This agenda looks very protectionist and isolationist so, if implemented, could be very damaging to the world’s open trading system and for the other, European, members of NATO who aren’t spending enough on defence. It may also embolden Putin and the Chinese Communist Party and encourage more geo-political turmoil and uncertainty. There is also the potential for turbulence associated with the sustainability of debt-financed growth in general and fiscal deficits, the US fiscal deficit in particular.

There was a mini bond riot in the summer with concerns about the US fiscal position but, given the scale of borrowing at a time when the US economy is strong, which normally is associated with cyclically strong tax receipts, there is the potential for a real hiatus over the coming years. To put this in perspective, the US Treasury needs to refinance 36% of the stock of public debt over the next 18 months or so, in addition to a $2 trillion fiscal deficit. The US does have the enormous advantage, or the ‘exorbitant privilege’ in the words of Valerie Giscard d’Estaing, of funding in US dollars – still overwhelmingly the global financing and reserve currency – but this may be a big challenge going forwards. Other countries don’t have these advantages, including the UK which is running persistently wide trade and fiscal deficits.

Similarly, there remains the potential for a Eurozone blowup over debt sustainability, one of the reasons we have low exposure to the region. Ukraine, the Middle East, and Taiwan all, of course, remain real potential flashpoints. Against all this, the climate continues to warm. We have followed the scientific literature for many years, but it is increasingly clear that we are very close to an irreversible tipping point on the climate on current policies.” [10]

Conclusion

We take comfort from the fact that Saltus portfolios are very widely diversified, we try and find many sources of return, that are each dependant on different factors, to reduce our reliance on individual companies, markets, asset classes, currencies, sectors (and politicians!). Saltus portfolios are typically much more global in nature than many we see (Saltus portfolios generally have less exposure to the UK), and so are less impacted by UK specific issues.

Saltus are watching events unfold, because there is a chance it is different this time, that politics may have an impact on financial markets and portfolios that requires action.

However, the lesson from history would be to block out the noise, not to worry too much about how politics will impact portfolios, however uncomfortable that feels.

For as Robert Arnott said, “in investing, what is comfortable is rarely profitable.”

Do you need help managing your investments?

Our team can recommend an investment strategy to meet your financial objectives and give you peace of mind that your investments are in good hands. Get in touch to discuss how we can help you.

In the above, I referenced the importance of economics for financial markets, so I thought I’d briefly summarise our view of the economic picture.

Our view of the current economic picture

Let’s look at some key themes

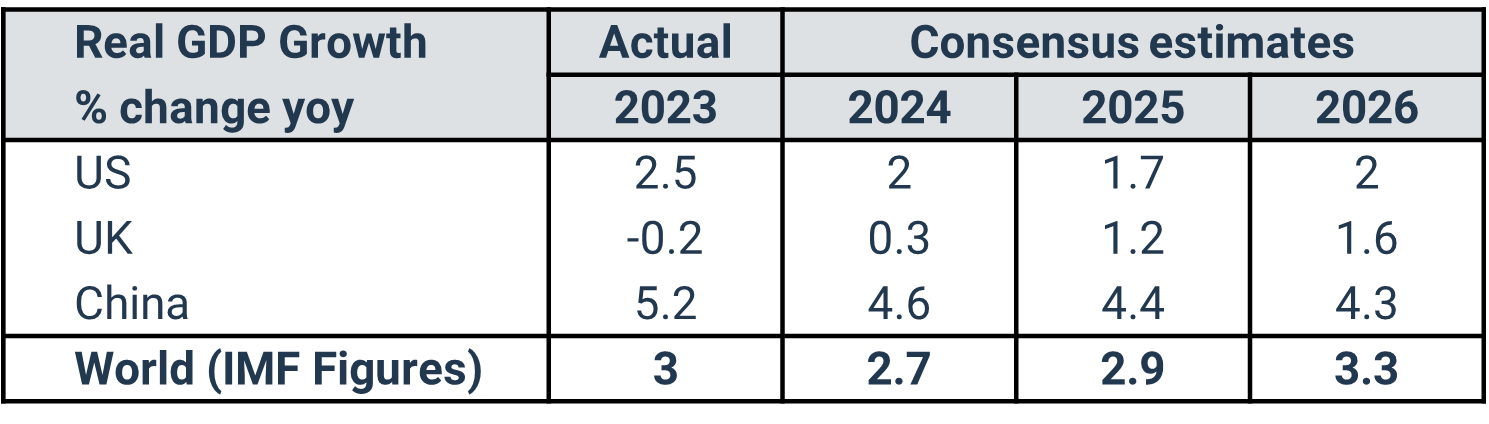

1. Economic growth – Below you can see economic growth for four selected areas, the US, UK, China, and the World. From 2023 (actual) and estimates over the next few years.

Source: Bloomberg

These numbers indicate gradual slowdowns, with more positive growth to look forward to soon.

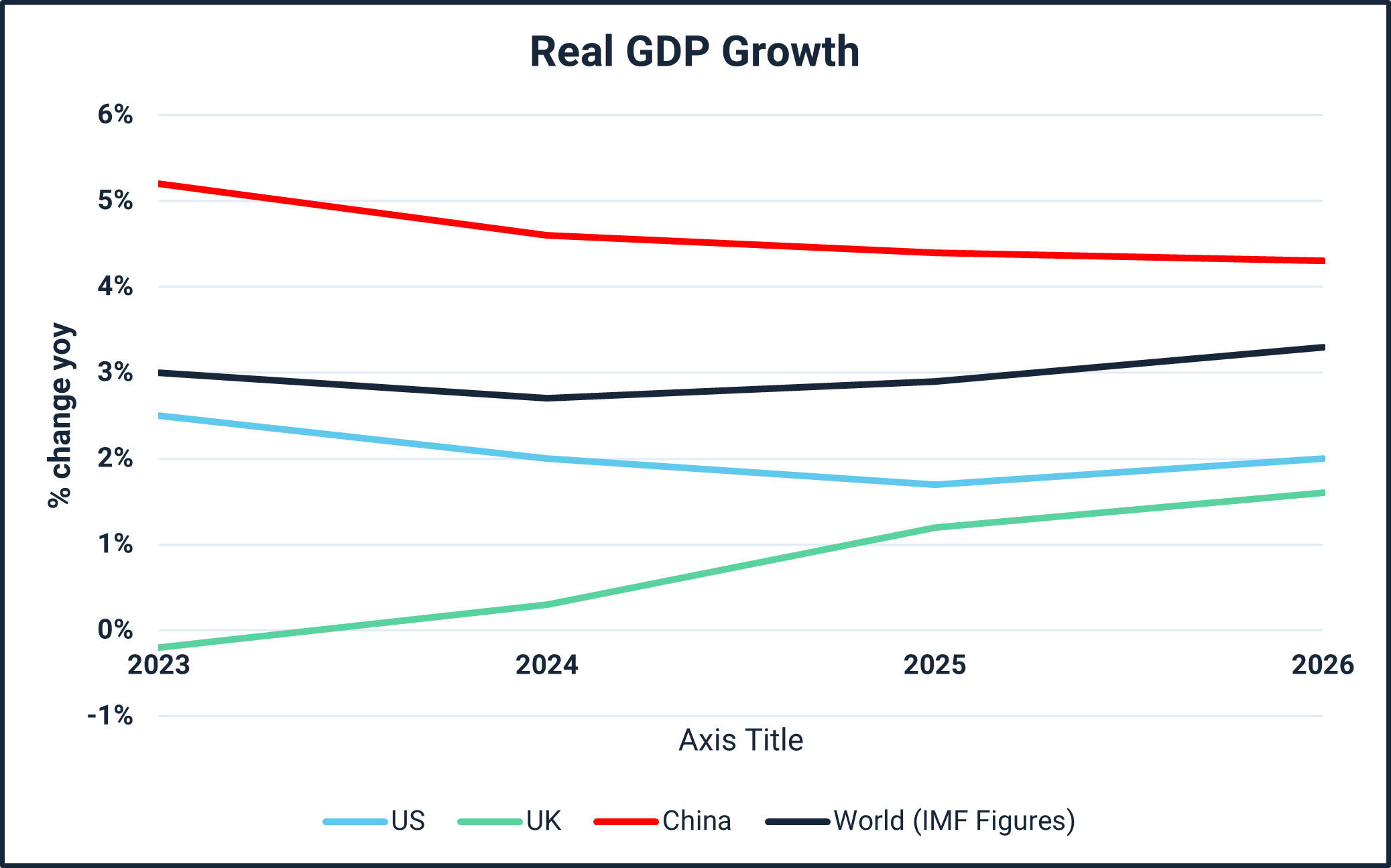

2. Inflation – To show you how much inflation has fallen over the last year, look at the white bars (annualised inflation numbers from January 2023) vs the blue bars (annualised inflation numbers from January 2024).

Source: The Economist, data for January 2024 and January 2023

Inflation has roughly halved in one year. We know the job isn’t complete (indeed some short term inflation numbers point upwards), and positive numbers still mean price rises (just smaller ones), but this is a very positive development.

3. Unemployment –See the IMF chart below, showing unemployment per country. The greener the country the less of a problem they have with unemployment. Lots of green on the board.

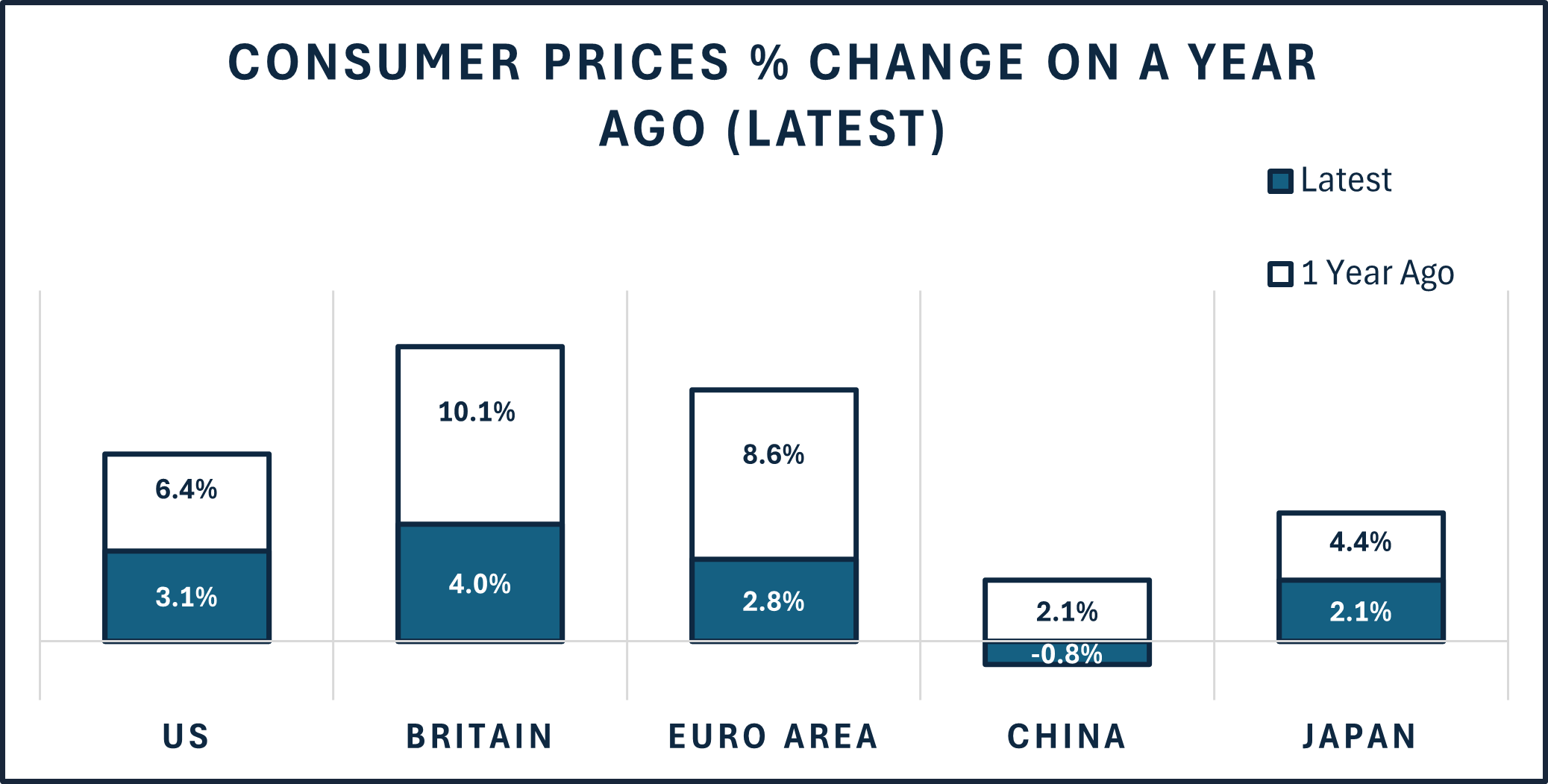

Indeed, globally, the unemployment rate is below recent averages.

Despite large increases in the cost of goods, labour and capital (pretty much everything then), unemployment has not increased significantly and remains low on average.

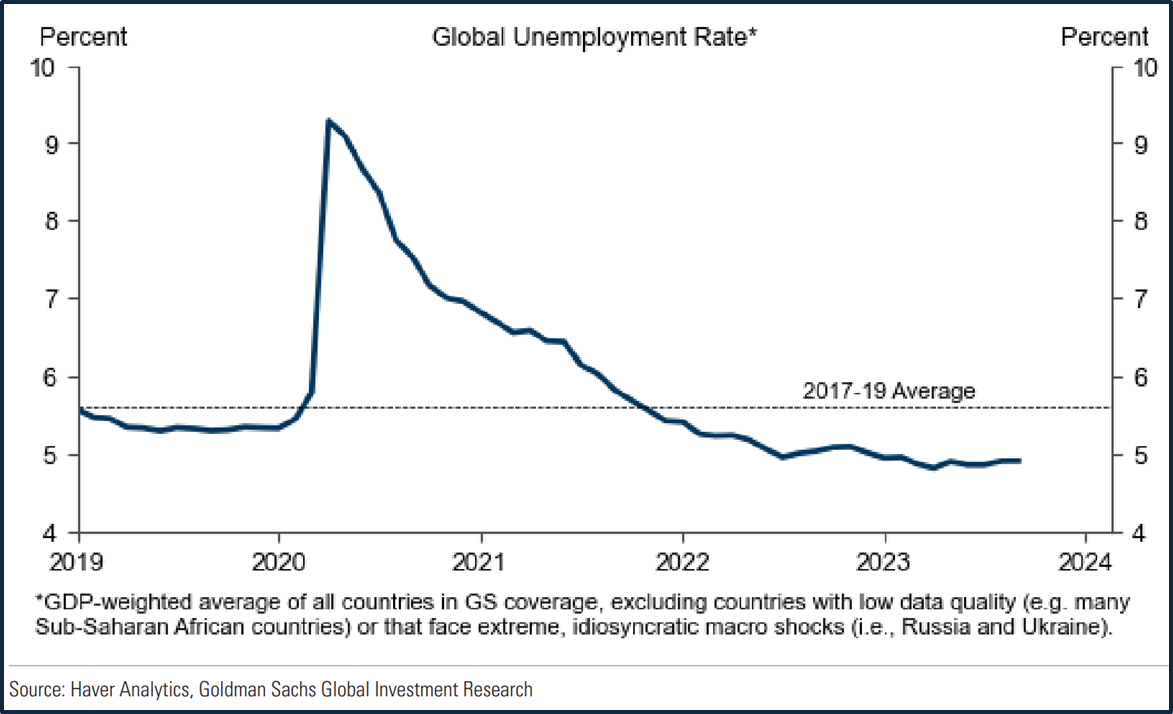

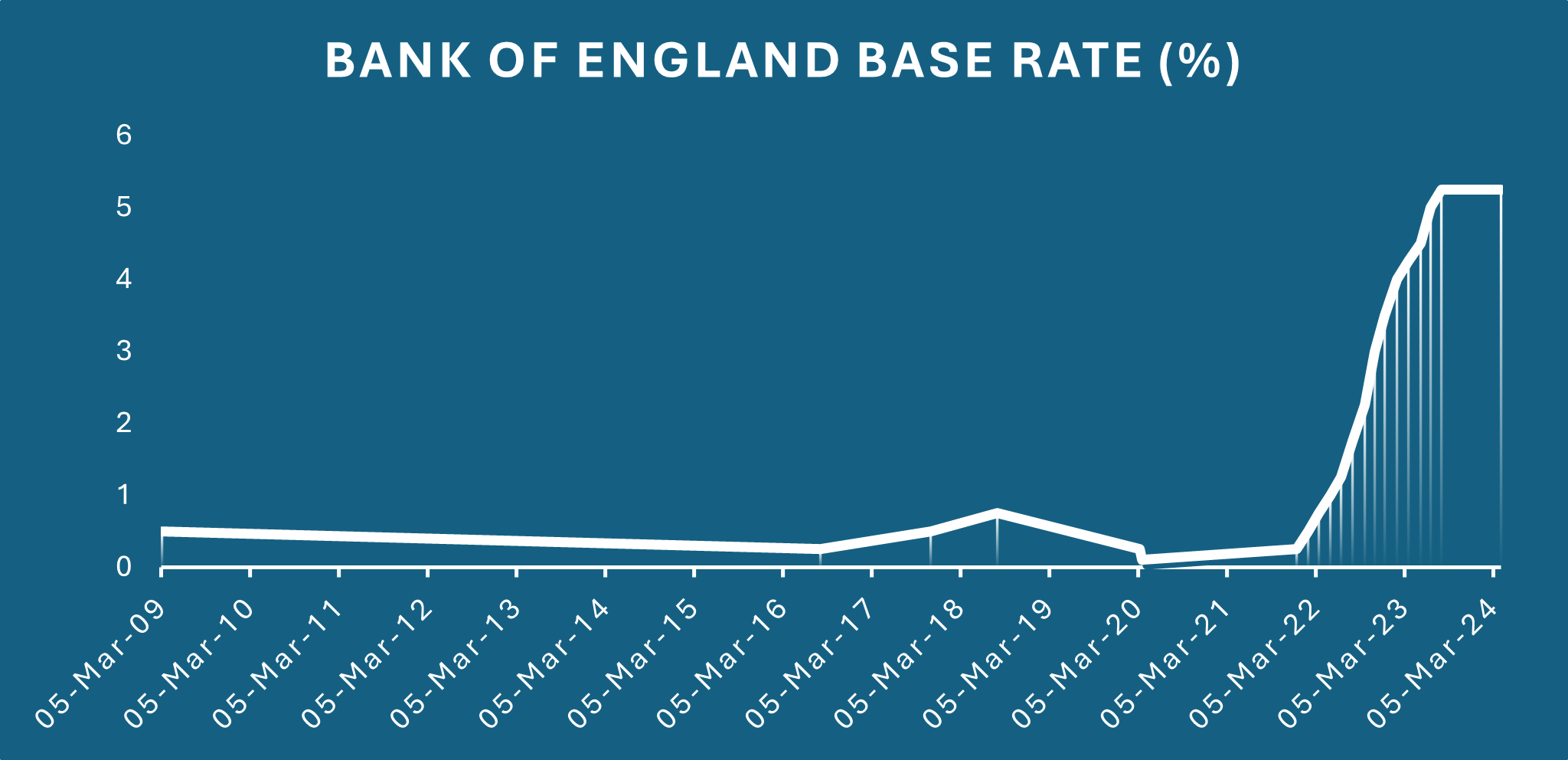

4. Interest rates – interest rates have increased. Quickly. In-fact, it’s been the fastest surge in the cost of capital in 40 years (according to Goldman Sachs). The chart below shows the recent surge in UK interest rates.

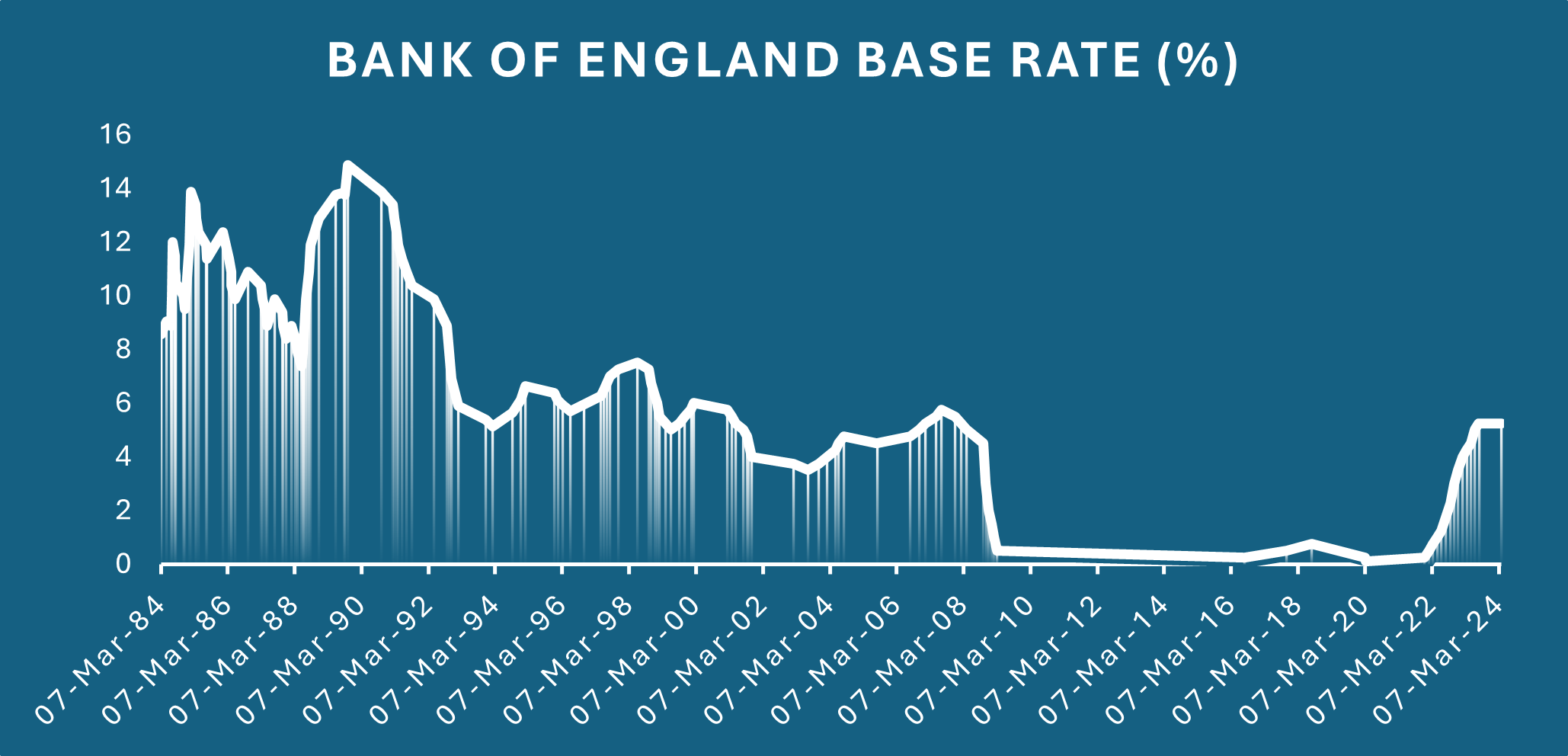

However, zooming out a bit (below). We can put the moves in more context (I’ve updated the date range to go back 40 years).

Interest rates were abnormally low post the Global Financial Crisis. They are now normal again. They’re also expected to start falling soon.

Article sources

Editorial policy

All authors have considerable industry expertise and specific knowledge on any given topic. All pieces are reviewed by an additional qualified financial specialist to ensure objectivity and accuracy to the best of our ability. All reviewer’s qualifications are from leading industry bodies. Where possible we use primary sources to support our work. These can include white papers, government sources and data, original reports and interviews or articles from other industry experts. We also reference research from other reputable financial planning and investment management firms where appropriate.